Heron Farms grows Salicornia and sources to local chefs

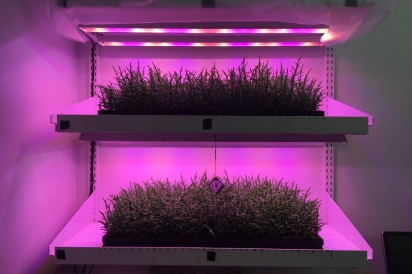

You might expect Sam Norton’s lab at the College of Charleston to be filled with tasty samples of Salicornia, the edible plant that’s the subject of both his master’s thesis and his various business activities. But in mid-December, the trays of plants surrounding him were not fit to be eaten. Some had been exposed to far too much light, their tips turned an odd shade of red; others had been overheated.

“This experiment is toast, and so is this one,” Norton says, gesturing around the lab. “Things mostly go wrong.”

That’s a pretty good summary of the practice of science, really: Failure creates new opportunities. And through that process of trial and error, Norton has been exploring the best ways to grow Salicornia for both food and environmental benefit.

Salicornia is a halophyte, orsalt-tolerant plant. And it’s an intriguing one, because it’s not only highly salt-tolerant, but also delicious. Varieties of Salicornia grow in salt marshes around the world. People in the Lowcountry know the local perennial variety, Salicornia virginica, as sea bean, sea pickle or glasswort.

Norton first had a taste of the plant on a kayaking trip in middle school. Years later, while studying science at the College of Charleston, he learned about a Boeing study in the United Arab Emirates using Salicornia grown in seawater to create aviation biofuel. He was stunned when he realized the plant in the study was the same one he’d been introduced to as a child—the plant that was growing all around him in Charleston.

He began exploring Salicornia’s possibilities locally. Specifically, he thinks it could be used to help restore the dredging sites around Charleston Harbor.

Look at an aerial map of Charleston and you’ll see vegetation-free areas along the water called confined disposal facilities, bordered by dikes and filled with sediment dredged from the harbor. Norton thinks Salicornia could help restore those areas to salt marsh. Marsh provides habitat for native plants and animals, stores carbon and protects against storm surges, among other benefits.

“This is the way the marsh fixes itself in nature,” he says, explaining how Salicornia helps create an area for the native marsh cordgrass called spartinato grow.

“Salicornia is called a colonizer or pioneer species. Its natural habitat is an intertidal zone that is hypersaline.”

He also thought he could find a market in Charleston’s restaurants. With its natural saltiness, Salicornia is unusual and delicious, just the local touch high-end chefs are looking for.

“Salicornia has a pleasant vegetal saltiness,” says Brett Common, baker and co-chef at hip Charleston pizza joint, Renzo, who likens his use of the plant to a finishing salt. He’s one of several chefs with whom Norton has shared his Salicornia harvest, looking for tips on how to grow and market it better.

“We used it as a garnish on a dish last summer featuring summer tomatoes and tonnato, and also baked some into our sourdough bread,” Common says.

James London, chef/owner of Chubby Fish, says he’d used wild-harvested Salicornia from California at previous restaurants, but having a local farmed source of the plant is a game-changer.

“It’s a vegetable that tastes of the merroir of the area,” he says. “What we do at Chubby Fish is dock-to-table seafood. Whatever’s coming out of the water that day, that’s what’s going on the plate and on the menu. With sea beans, it’s a vegetable that tastes of our waters. It really makes that plate special.”

But before he could start selling his Salicornia to chefs, Norton had to figure out how to farm the plant effectively.

One of Norton’s early experiments involved growing Salicornia in its natural habitat, in the marsh. But that approach didn’t make much sense from an agricultural perspective.

“You can’t till, you can’t amend the soils, it’s hard to get high germination rates because of the salinity,” he says. “It just doesn’t make sense commercially. It does make sense for restoration, but it doesn’t make sense for food.”

Next, he tried growing the plant hydroponically outdoors, pumping seawater into troughs.

“I didn’t know what I was doing,” he says modestly. “I still don’t. But it turned out all the plants grew and were happy and healthy.”

“That was when we first realized, ‘Oh my god, this is going to work.’”

”Early on in his experiments, Norton was awarded a grant through what was then a brand-new South Carolina Department of Agriculture program called the Agribusiness Center for Research and Entrepreneurship, or ACRE.

“The ACRE Entrepreneur Program was created to seek out and assist innovative agribusiness entrepreneurs in South Carolina,” says Kyle Player, ACRE’s executive director. “We knew these entrepreneurs were in the state and on the cusp of a successful business but needed a little assistance, whether that be funding, business plan help or introductions to resource providers.”

Player says Norton stood out.

“Sam’s farm, pitch and business plan was the most innovative and forward-thinking of the 26 applicants,” she says, calling him “a great ambassador for ACRE.” He received $50,000.

More recently, Norton won funding through The Harbor Entrepreneur Center. But ACRE was a key early supporter, he says.

“It started as me trying a bunch of different things and ACRE saying, ‘OK, dude, you can do this. Go try to figure this out.’”

Through further experiments, Norton determined that he needed to grow Salicornia indoors for culinary uses. When the plant flowers, it produces bitter compounds. Growing inside allows him to stop the plant from flowering so frequently, and to grow it more efficiently. So, starting this year, Norton will be partnering with Amplified Ag, the Charleston-based parent company for Vertical Roots, which grows lettuces in upcycled shipping containers. He’s been lining up restaurants in Charleston and elsewhere willing to become regular customers.

Heron Farms has also gotten some attention from brewers. Low Tide Brewing Co.’s Coastal Harvest Gose is made with Norton’s Salicornia—an ideal match, as traditional goses are brewed with salt.

As Norton prepares to launch into full production mode growing Salicornia for wholesale, he’s also working on ways to use Salicornia to help restore the marsh. With help from the Charleston Fablab, he’s just finished building a drone to disperse Salicornia seeds over a confined disposal facility for an experiment testing whether Salicornia can speed up the removal of saltwater from the dredged sediment.

He’s still captivated by the strange, salty, succulent plant, he says. It’s only natural.

“We’ve evolved to like salt, which is pretty cool,” Norton says. “You can catch a deer or wild boar by putting out a block of salt. It’s because we need salt for our brains to send electrons through our nerve cells to transport ions.

“And Carl Sagan says in this book”—he points at one of the books stacked under the computer monitor on his lab bench—“that the reason we love to look at the ocean is the reptilian part of our brain remembers we crawled out of there a while ago. I always loved that.”